Remember: you can click on any image to see the full-size version, and click “back” to return

A musical interlude

I’m not very musical by nature, but in my humble opinion Peter Gabriel had “rather a lot to say”. In particular, I think his “Secret World” performance is a masterpiece. In one of my least-favourite parts of it, he croons:

we’re digging in the dirt

to find the places we got hurt

I think Mr. Gabriel was expressing something that most people (not just scientists) know through experience. There’s no such thing as a perfect anything…but successful humans and organizations strive to learn from mistakes.

Stuff happens

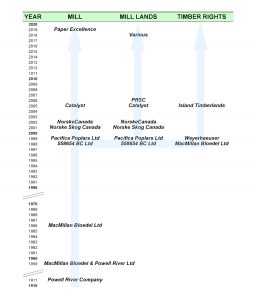

Take me, for example. Having tried to build an accurate history of “Lot 450”, well, I still get surprised occasionally.

It wasn’t the document that surprised me.

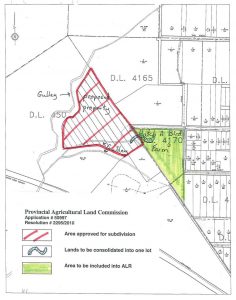

But the shape of the land-parcel did.

Consider the image above, which was recently posted on Facebook. It didn’t make sense to me. I’ve been studying these exact same land parcels for years…so to me it looked like a big bite had just been taken out of the southeastern corner of the upper parcel.

I’d looked at this document before, but hadn’t realized that a land SALE was involved.

What is this…Shark Week?

Thus I learned about another land sale by PRSC. The details are simple enough. PRSC sold 13.5 acres to Hatch-a-Bird Farm back in 2010. As part of the deal, land was added to the ALR.

My Facebook informant helpfully reported that the ALR inclusion was a “condition of sale”.

Aha. Because the sale involved ALR lands, an application was required – and a decision was made. I’d seen that decision before, but confess that I hadn’t connected-the-dots (or georeferenced the map).

Fundamentally, what this meant for me is that I needed to fix all my date-stamped maps. Much cursing and gnashing of teeth ensued.

Oh well.

Hopefully the revised PRSC “land story” is more accurate than it was.

Digging into the books

Elsewhere I’ve written about the desirability of having a “full accounting” of the PRSC experience. I’m not alone. Enter Pat Martin, who’s been pestering City Hall with Freedom-of-Information (FOI) Requests since she first appeared as a “Delegation” before the Committee of the Whole in January of 2019.

Pat has achieved some remarkable success. For the first time we now have PRSC’s financial books. Or, more accurately, we have copies of their two sets of books. Here they are:

– PRSC Land Developments Ltd – Financial Statements

– PRSC Limited Partnership – Financial Statements

Now if you’re like me, at first glance having two sets of books doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Then I thought about it some more. Perhaps it’s like maintaining separate life-tables for males and females in a wildlife population – there might be sound reasons behind this division that are not easily appreciated by a layperson. I accept that there might have been some reasons for this division – and I doubt we’ll ever learn what they were.

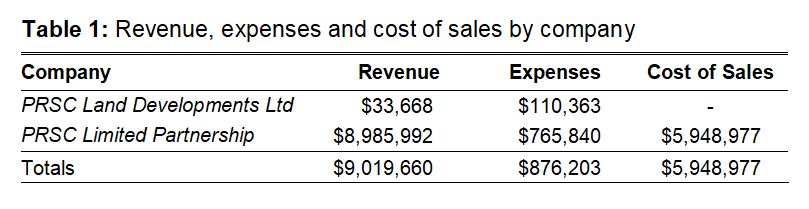

It doesn’t matter. There are more interesting things to be found in the financial statements. I began by calculating some basic statistics as follows:

The first obvious conclusion from this is that PRSC Land Developments Ltd never sold any land. Indeed this was the much smaller of the two PRSC entities, reporting a total of only $33,668 in “revenue” and $110,363 in “expenses” over 13 reporting periods (the PRSC “fiscal-year” ended on 31 March – and the first and last reporting periods were not “full years”).

PRSC Limited Partnership was the much bigger brother, with close to $9 million in revenue, $876,203 in expenses…and a whopping $5,948,977 in “costs of sales”.

So taken as a whole, the combined PRSC enterprise showed a net profit of $2,194,480 from 2007 through 2018. So far so good.

When did PRSC become profitable?

The numbers are combined totals from the PRSC Limited Partnership and PRSC Land Developments Ltd.

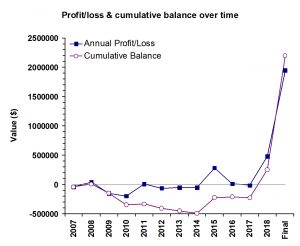

Here’s a time-series with two variables. Specifically, I’ve plotted annual “profit/loss” and a calculated “cumulative balance” against “fiscal year”.

This is quite revealing. Apart from a small positive “blip” in 2008, PRSC carried a negative balance until its final year of operation in 2018.

I’ll say it again: PRSC only became profitable in its final year of existence, after previously-unsold lands were acquired by the two remaining partners.

I’m still confused by this.

Did money actually change hands in 2018? Or was the “appraised value” of land used to create the appearance of a “profit” at time of dissolution?

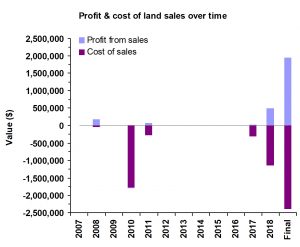

Land sales and profits over time

Now that an “end-of-game” scorecard has been obtained…

How much did PRSC actually earn by selling all those ex-Catalyst “surplus” lands?

This graphic omits “revenue” reported as “cost recovery” or “forfeited deposits” in 2015 and 2016.

The bottom line is that it cost $5.9 million to sell lands worth $8.6 million.

I explored this question by focusing my attention upon the Limited Partnership and selecting only those fiscal years in which “costs of sales” were reported.

In scientific terms, I “constrained the sample”. Thus I ignored revenues from “cost recovery” (FY2015) or “forfeited deposits” (FY2016). I don’t know what those mean, and I wanted to compare apples with apples.

There were six years in which PRSC reported “costs of sales”. The bad news for PRSC shareholders is that these costs were 69% of the gross value of the lands. In 2010 they lost money (-$20,427) on lands that sold for $1.76 million. In 2017 they earned only $16,939 from the $330,000 sale of Wildwood Hill (this represents the only instance in which it’s possible to tie revenues to a particular land sale).

I’m frankly dumbfounded by figures such as these – but maybe there’s a reasonable explanation. Unfortunately the financial statements provide no details about how “costs of sales” were calculated. The bad news for me is that I’m unaware of any land sold in 2008, but the data suggest there was – so I may be needing to update all my date-stamped maps again when that information becomes available…

aaargh

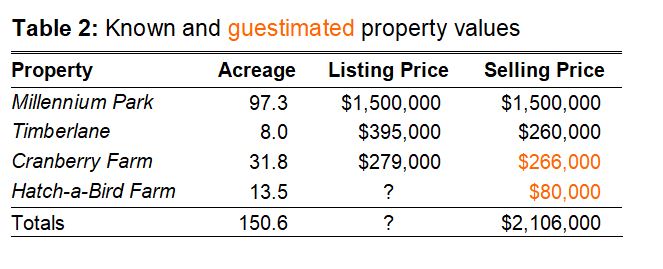

Filling in the blanks

The financial records unfortunately don’t break down revenues by property. Period. The result is that it becomes impossible to ask questions about “good property deals” versus “bad ones”. Nor is it simple to reconcile financial records with those from other sources. A few examples will illustrate the difficulties.

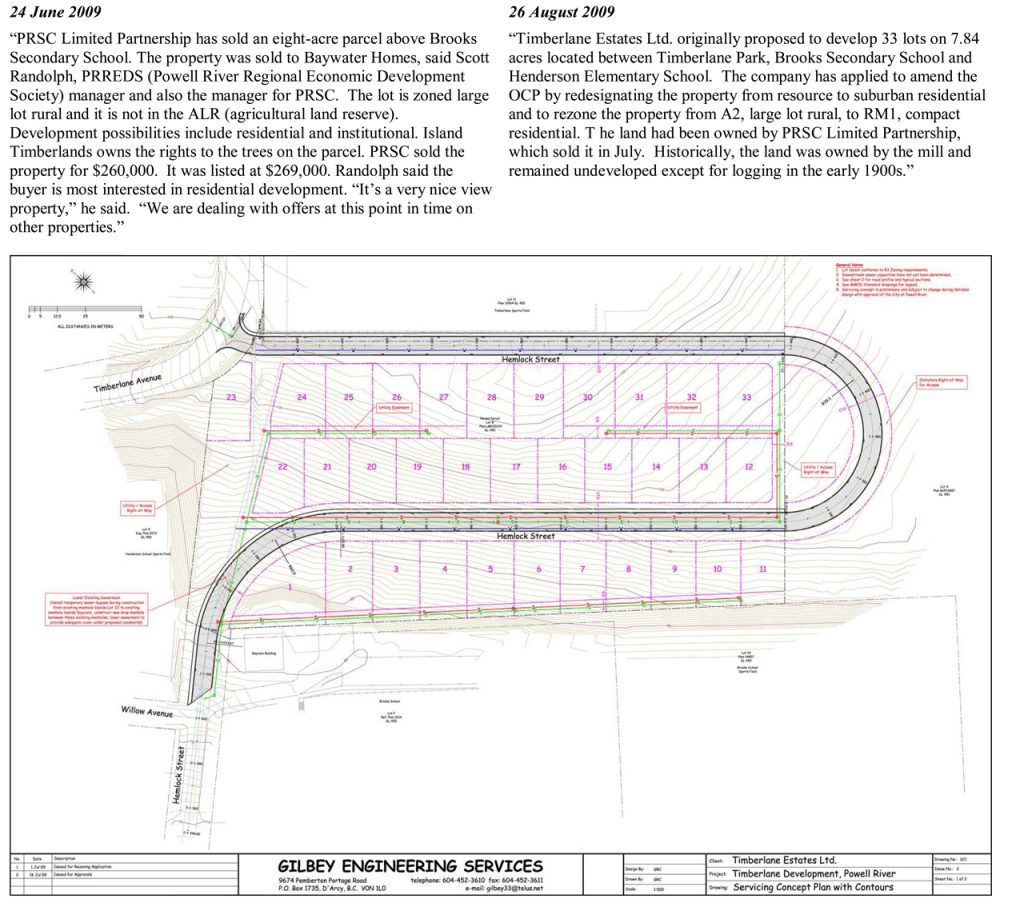

We know, for example (from the MLS listing) that the property that became Timberlane Estates sold on 10 March 2009 for $260,000. This sale doesn’t show up in the FY2009 report for the Limited Partnership, even though their “fiscal-year” ended on 31 March.

The FY2010 report shows that year to have been a relatively good one – with $1.76 million worth of sales. Approximate dates are known for some of these sales. Millenium Park sold in 2010 (the Peak announced it on Feb 10th), as did the 32 acre “farm in Cranberry” (the Peak reported that on Jul 21st), and Hatch-a-Bird Farm (Facebook in 2019).

Allowing for some delay in “the paperwork catching up”, I think it’s reasonable to make informed guesses about what must have happened. Accordingly I pooled the data for FY 2010 & 2011 revenues, looked at the listing and selling prices for the properties that I knew about, and guessed at the ones I didn’t. The result looks like this:

That gets me pretty close to the reported total of $2,106,550 for the two years. None of it, however, explains the ginormous costs of sale ($2,057,035) or the puny profit that ensued ($49,515).

That gets me pretty close to the reported total of $2,106,550 for the two years. None of it, however, explains the ginormous costs of sale ($2,057,035) or the puny profit that ensued ($49,515).

Will it ever end?

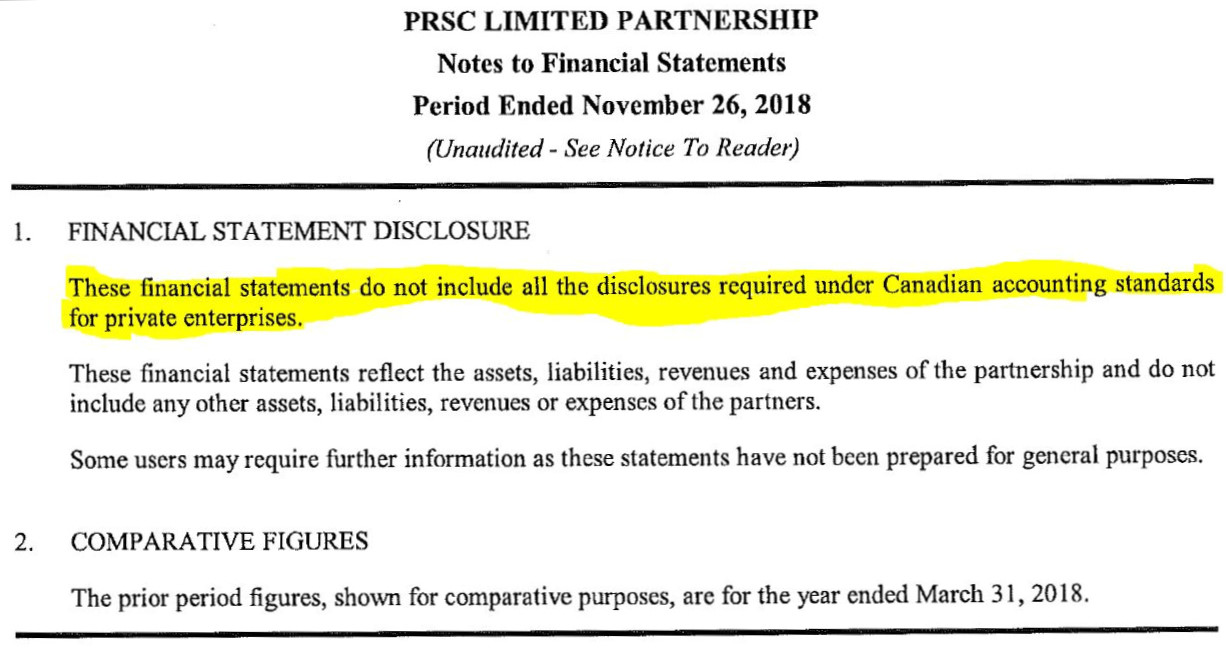

There are numerous other oddities and inconsistencies to be found throughout the PRSC financial records.

There’s a substantial accounting error in the 2018 PRSC Land Developments Ltd statement caused by adding two negative numbers incorrectly. The value of the PRSC “Land Inventory” goes up in some years – by adding the cost of property taxes paid. Yes. You read that correctly.

I note that the PRSC financial statements were audited for only two of the 13 reporting periods (FY2007 and FY2008). Subsequent statements were unaudited and contain wording like this – a situation I don’t find comforting at all.

So I think some kind of a retroactive audit is long-overdue…if for no other reason than to save us from doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result.

In essence? Having explored things in some detail, I think the taxpayers of Powell River got hurt.

PRSC was ill-conceived and sloppily managed. There were promises but no real attempts at “transparency”. It shouldn’t have taken FOI requests to obtain financial records, it shouldn’t have needed “social media” to learn about land sales in 2010, and it shouldn’t have been possible to build a road on the ALR to service the neighbour’s housing development…especially when the “neighbour” was also a “Founding Director”.

I remain saddened that we collectively seem to want to avoid recognizing the fact that these were mistakes

– and we might learn from them.

Meanwhile, Peter Gabriel is still digging …in my head at least.