9 November 2015

The ALR

Mention the ALR in Powell River and you’ll likely evoke strong reactions – some love it, some see it as an impediment to development, and some see it as yet another great idea mis-managed.

Me? I’m reminded of Aldo Leopold, who wrote:

“There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.”

The farm

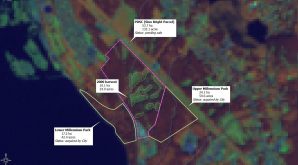

On this map the brownish areas are rated as “poor”, blue-grey areas are rated as “fair”, and dark green and teal-colored areas are “good” (improvable to Class 1 or 2).

To begin: the agricultural potential of the Sino Bright parcel is modest.

Madrone’s 2007 land capability report is thorough and credible. A portion (40%) of the area contained “good” agricultural soils (i.e., improvable to Class 1 or 2). The majority (53%) was rated as “fair” or “poor” (improvable to Class 3 or 4).

In short, this is not prime agricultural land. Especially if you view farming as having to be large-scale, or mechanized, in order to be successful.

That’s nonsense, of course – there are all sorts of ways to successfully farm smaller areas, even in tiny Powell River.

Personally, I suspect that opportunities for mechanized farming were greater on the 112 ha that was excluded from the ALR in 1994 – precisely because it’s flatter. But I digress. My point is that the Sino Bright parcel is functional agricultural land, for reasons that Aldo Leopold would have fully appreciated – because it’s being used to grow trees.

Well, it’s sort of being used to grow trees. Here’s where history intervenes, and things get complicated.

Some history

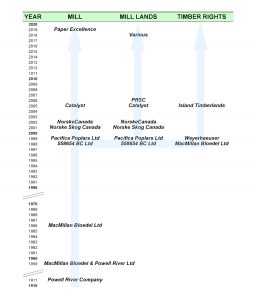

In particular, the demise of MacMillan Bloedel Ltd in 1998-99 saw the unusual separation of land ownership and forest ownership.

[UPDATED Sep 2019]

However, timber harvest rights have been considered separately since 1998, when MacMillan Bloedel restructured itself. In this case the flow of timber rights was from MacMillan Bloedel to Weyerhaeuser to Island Timberlands.

For this reason the current (PRSC) or future (Sino Bright) landowner has little control over forests, or the timing and methods of harvesting. It’s akin to buying a farm without control of the crop.

I recognize that the Land Commission’s mandate is not to evaluate how well landowners have maintained the integrity of agricultural lands or invested in their future potential. Their job is to a) preserve agricultural land, b) encourage farming on it, and c) encourage local governments to do the same.

The furnace

About 22% of the Sino Bright parcel (and 25% of the standing timber) was logged between the two dates.

Two things caught my eye while exploring this particular land parcel. Specifically, its agricultural potential has already been degraded.

The first problem stemmed from logging, in this case by MacMillan Bloedel and Weyerhaeuser, in 1999-2000. The logging itself is not the issue. I have no problem with thinking about forests as a crop – indeed that’s why we have a “tree-farm license” system in BC. From my perspective this is a good idea, especially if it encourages the maintenance of forests, forestry workers, and biological diversity.

Sadly, however, in this instance (and in many others in the region), clearcutting and removal of wood was followed by…nothing. The land was neither replanted nor tended with forestry values in mind.

So instead of a healthy young crop of fir, hemlock and cedar, these areas are now overgrown with red alder and blackberries. When asked their opinion of the harvested patches and what they’d advise doing with them, two foresters who walked with me expressed the same opinion: “mow it down and start afresh”.

Because I’m an ecologist who understands the value of early successional forests, I don’t think I’d go so far.

But their opinion does underscore my point. Some 16 years after harvest, a substantial portion of the area is not what it could have been.

Or to use Aldo’s words…

…the land is not being used to its full potential, providing for breakfast or the furnace.

The language of the original timber License is quite explicit:

“The Licensor acknowledges that the Licensee has the full right and privilege to harvest and remove the timber growing on the lands as of May 31, 1998. A harvesting plan is to be reasonably agreed to between between the Licensee and the Licensor.”

The agreement further states that upon termination, the lands and roads will be left “in a condition reasonably acceptable to the Licensor” and that

“Once the timber has been harvested in accordance to the agreed upon harvesting plan and removed by the lands by the Licensee, this license and all rights inferred will terminate. Any remaining timber not harvested by the Licensee at this time will belong to the Licensor.”

One would assume that the terms of the license were fulfilled – i.e., that there was a harvesting plan “reasonably agreed to” by Pacifica Papers (the Licensor in June 1999) and Weyerhaeuser (who acquired the Licensee MacMillan Bloedel Ltd in November of that year) – prior to any trees coming down.

The future is growing

So I remain puzzled by the subsequent grant of timber rights by Norske Skog Canada to Weyerhaeuser in June of 2005 – with no mention of the fact that the Licensee had already exercised their rights by cutting 1/4 of the standing timber. I’m puzzled also that Weyerhaeuser, which advertised itself as the “tree-growing company”, had not replanted the land – or seemingly been asked to do so by the Licensor.

Was the “reasonably agreed to” harvesting plan in 1999 just considered to be incomplete in 2005?

As in “sure, my company can mow your lawn…we’ll do the easy bits now, then come back later to finish up… maybe in five years time…or fifteen years…or whenever we feel like it”.

Really?

I suspect we’ll never see details of the agreed-upon harvest plan. It was likely just an annotated forest cover map, with some notes about road access. Some might consider that this is old news, and doesn’t really matter. I would argue that it very much does matter, because it comes down to a question of what the future may hold for a parcel of land that still contains substantial forest values.

Another problem

The second problem was something that at first I thought was the GIS version of a “typo”. What I’d noticed, after comparing Landsat imagery and ALR maps, was something odd.

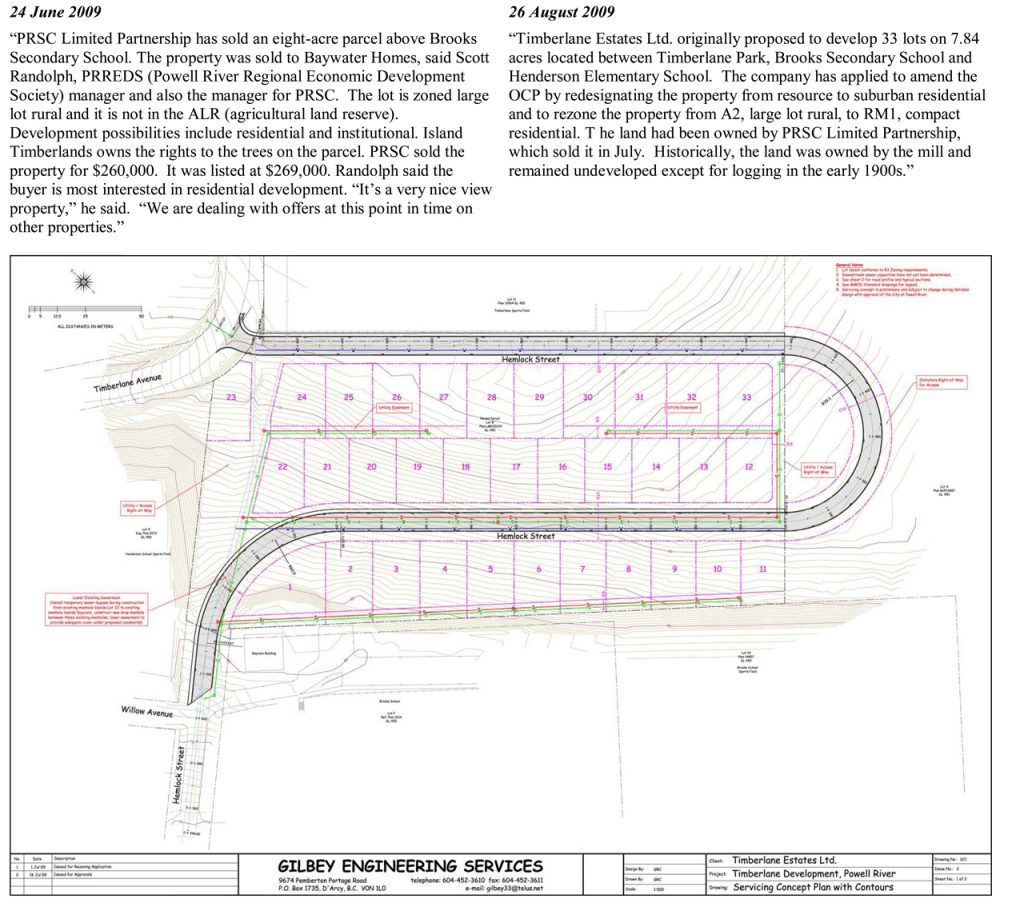

As can be seen on an image from 2011, the semi-circular loop road at the top of Hemlock Street was constructed on the ALR.

Had a paved municipal road really been constructed on the ALR? Yes. Could I be certain of when it was constructed? Yes. Was there an application related to it, or a decision made about it? Well, not that I can find.

Construction of the road amounted to an “effective” ALR exclusion size of about 0.8 ha (1.8 acres).

The Powell River Peak again provides essential context (sadly, many of their online archives have disappeared).

One article described the land sale, and a follow-up story provided more details and a map of the planned subdivision. From these it’s apparent that the road was part of the design from the very start.

– but seemingly the ALR was forgotten about in the planning process.

At this point it’s impossible to be certain about why or how this happened. But it did, and it means that in terms of the subdivision for which 8 acres were sold by the PRSC, about 10 acres were actually used to develop it.

Yes, more nibbling away at the ALR – Powell River style.

It is rather a nice road…but somehow I think Aldo would be unimpressed.